Africa air travel: The road to airspace liberalization

This is a prelude to part II of The Conquest for the African Airspace: The movers and shakers. In this article, we review the journey thus far in the liberalization of the African airspace.

Introduction

Air transportation is not only a crucial element for regional economic growth but also plays a pivotal role in ensuring timely deliveries and reducing travel times. The significance of air travel lies in its ability to open up and connect countries and markets, thereby stimulating passenger traffic, facilitating the smooth flow of trade and foreign direct investments, and providing access to global supply chains. Consequently, it fosters economic development and, most importantly, enhances regional integration.

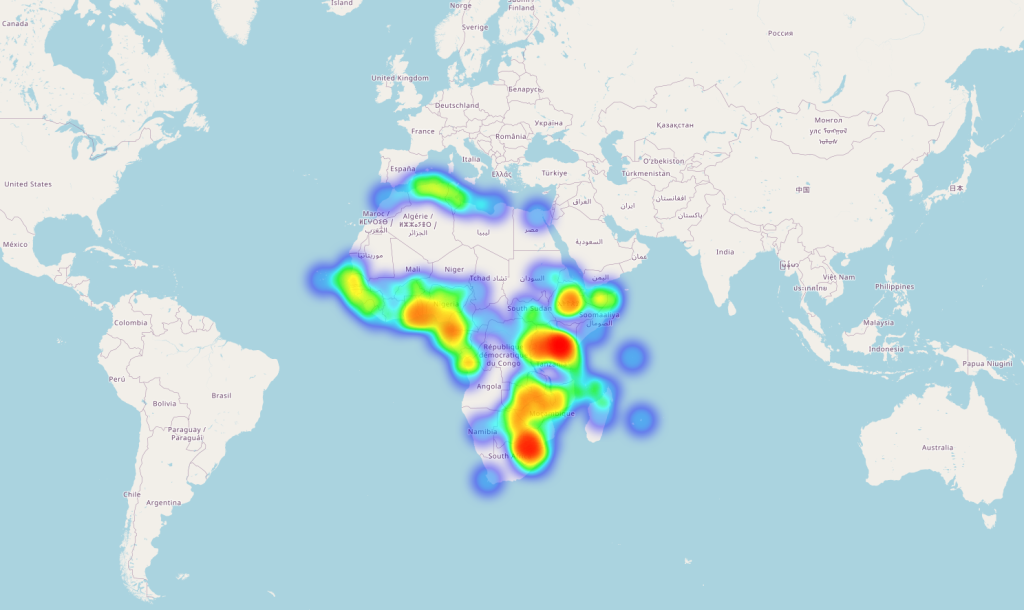

However, numerous urban regions in Africa face challenges when it comes to airline connectivity, both within the continent (intra-continentally) and in terms of international connections (inter-continentally), as discussed in the first part of this article. Consequently, Africa’s overall performance in global and transnational urban air connectivity falls below the expected standards. When compared to the rest of the world, air transport volumes within the African continent are significantly lower, with an intra-air-connectivity penetration rate of only about 14.5%. To provide some context, even though sub-Saharan African countries have a population more than five times that of Brazil, their airline passenger volumes are lower than those of Brazil.

There have been various explanations put forward to account for the lack of air transport connectivity in Africa. One such reason, although it may sound absurd, is the prevailing perception of air travel as a luxury rather than a means of transportation. Consequently, it has been regarded as a privilege reserved for the affluent and privileged members of society. This perception holds some truth, considering that air travel within Africa is comparatively expensive, with costs approximately 45% higher than the global average. The African Airline Association (AFRAA) report for 2021, for instance, highlights that African air travellers pay an average of $50 in taxes, whereas travellers from Europe and the Middle East pay $30.25 and $29.65, respectively, for flights covering the same duration.

The irony lies in the fact that the average monthly salary in Africa is ten times lower than that in the United States and the United Kingdom. According to World Bank data from 2019, an estimated 85% of Africans survive on less than $5.50 per day. Furthermore, the preferred modes of transportation, namely surface transport options such as roads, ports, and railways, are limited in their capacity due to poor maintenance. This limitation often hampers the safe and efficient transportation of both goods and people.

Another reason behind the poor air connectivity in Africa pertains to the demographics of its population, which is predominantly dispersed in sparsely populated rural areas. Unfortunately, the benefits of improved air transport are primarily experienced in urban regions and developed areas. While the validity of this reason may be subject to debate, it does not significantly contribute to resolving the intra-Africa connectivity challenge.

Consequently, the main factors responsible for Africa’s inadequate air connectivity are related to state ownership, protectionist tendencies towards local industries and national carriers, and the absence of route liberalization. Folly-Kossi, a former Secretary General of AFRAA and an aviation consultant, identifies these factors as impediments to intra-Africa air travel. He also highlights the excessive ambition of countries to establish their own national carriers at any cost. From his perspective, African nations regard the flag, the national anthem, and an airline as integral symbols of sovereignty.

On the other hand, trade within Africa faces significant limitations. Intra-African trade, which refers to the average of exports and imports between African countries, has remained remarkably low. According to the UNCTAD Economic Development Africa report for 2019, during the period from 2015 to 2017, intra-African trade accounted for a mere 2% of the world’s total, despite Africa being a significant net exporter of raw materials across various categories. In comparison, Europe recorded figures of 67%, Asia 61%, Americas 47%, and Oceania 7% during the same timeframe.

Nevertheless, when it comes to the future of the African airspace, there is cause for optimism as highlighted by both the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Air Transport Association (IATA). Africa has been identified as the continent with the highest potential and opportunities in the aviation sector. This is attributed to the continent’s rapidly growing population, which represents approximately 16% of the global population, as well as the transformative effects of globalization and liberalization on the industry.

However, despite the promising growth forecasts for aviation, intra-African markets lack depth, and the different regions of the continent are at varying levels of economic development and stability. Furthermore, the number and extent of commercial bilateral air service agreements between African countries vary significantly, further hindering seamless connectivity within the continent.

Road to the liberalization of intra-Africa air travel

Prior to achieving independence, the air transport requirements of Africa were primarily fulfilled by the European powers of that era. Consequently, certain international airports and airlines in Africa have their origins rooted in the colonial period. As a result, intra-African air services during that time were primarily based on European relationships and agreements. Furthermore, the airlines operating in African airspace were either owned or operated by the colonial governments or their affiliated companies.

Upon gaining independence, the newly sovereign African nations assumed control over the airspace above their territories. They embarked on negotiations and the establishment of their own commercial bilateral air service agreements (BASAs). These agreements were aimed at strengthening the position of the newly formed government-owned national airlines, often motivated by a desire for prestige. However, it is worth noting that many of these airlines did not achieve significant operational success or take-off as intended.

So, what led to the failures of most of these national airlines?

The answer can be found in their ownership structures and business models. Firstly, the majority of these airlines were state-owned, meaning they were operated as government entities. Consequently, they lacked the necessary economic and commercial focus required for market viability and profitability. These carriers often exploited the limitations imposed by BASAs, using them as a means to restrict traffic rights for foreign airlines. Paradoxically, these same states often lacked the technical, human, and financial resources to develop or implement proposed new route networks themselves.

Turning to their business models, these carriers primarily focused on intercontinental routes between the newly independent African countries (acting as airline hubs) and their former colonial powers. However, these routes were highly competitive, as the former colonial government-owned carriers still maintained a strong presence. Despite granting sovereignty, these colonial carriers ensured that the newly established BASAs did not significantly impact their own operations in these markets. This created a severe threat to the survival of the emerging African airlines. Meanwhile, the development of intra-African route networks, which could have provided alternative opportunities, was neglected and remained underdeveloped.

The regional routes and the African market as a whole were considered secondary and of lesser importance by the governments at the time. This was primarily due to limited trade among neighboring African countries and the fact that the raw materials produced in these African nations were primarily destined for destinations outside the continent. Conversely, imported finished products were transported back to Africa. As a result, the focus of these carriers was primarily on establishing intercontinental route networks.

In line with the nationalistic economic policies pursued by independent African states, the commercial BASAs of that era adhered to a traditional model. This model predetermined market entry and exit, network capacity and frequencies, ownership regulations, tariff requirements, and pricing restrictions. These measures enhanced government control over the markets and effectively limited airline competition. Even to this day, commercial air service agreements in Africa are still a work in progress, undergoing continuous refinement.

However, a significant turning point occurred with the introduction of the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 in the United States. This act brought about an unprecedented transformation in the air transport industry. The subsequent removal of government controls and the implementation of privatization policies, as a result of airline deregulation in the US, led to substantial growth in airline connectivity. Following the liberalization of US airspace, the European Union (EU) introduced the Single European Act in 1986. This act eliminated barriers to competition within Europe by granting European carriers the freedom to operate on any route within EU airspace without capacity restrictions. Furthermore, airlines were given the flexibility to set ticket prices based on prevailing market conditions. The results were remarkable, including an increase of up to 88% in route options, a reduction in airfares by approximately 15%, and a doubling of aircraft seat capacity.

Initiatives to liberalize African airspace

Africa was not willing to lag behind in the wave of air transport market liberalization. Recognizing the importance of unified liberalization of air service agreements (ASAs) alongside individual BASAs, African states realized the need to promote air travel within the continent. The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), through the Economic Commission for Africa, took up the task of identifying the need for policy changes to support the development of Africa’s air transport sector. After extensive deliberations, declarations, and resolutions, the Lagos Plan of Action for the Economic Development of Africa (1980-2000) was established. This plan aimed to reduce Africa’s dependence on the Western world and foster the integration of transport and communication infrastructure to facilitate increased intra-African trade. Its primary objective was to remove both physical and non-physical barriers that hindered the development of intra-Africa air travel.

In 1984, a conference was convened in Mbabane, Eswatini, by UNECA’s economic commission for Africa to address the challenges faced by African airlines in obtaining traffic rights to other African countries. During this conference, an important declaration known as the ‘Mbabane Declaration’ was made. The declaration called for the creation of a technical committee tasked with developing a unified African approach to facilitate the exchange of third and fourth freedom rights. Additionally, it encouraged the exchange of fifth freedom rights and fostered closer cooperation between African carriers.

These proposed measures subsequently formed the essence of the ‘Yamoussoukro Declaration’ of 1988, named after the city in Cote d’Ivoire where it was agreed upon. This declaration encompassed various agreements, including the establishment of a joint financing mechanism among African states, coordination in scheduling air services, the creation of a centralized databank and research program, as well as the formation of sub-regional airlines. The ‘Yamoussoukro Declaration’ itself represents a multilateral agreement among African countries, with the aim of facilitating the exchange of fifth freedom air traffic rights among the 44 signatory members.

A decade later, in 1999, the ‘declaration’ was elevated to a ‘decision’ after it was adopted by African ministers responsible for civil aviation. This decision was made in recognition of the detrimental effects of protectionism on national (flag) carriers, including compromised air safety records and inflated airfares that hindered the growth and development of intra-African air travel. In July 2000, the revised ‘Yamoussoukro Decision’ received endorsement through a unanimous vote by the assembly of heads of state and governments of the Organization of African Unity (AU). The declaration became fully binding in 2002, with the overarching objective of fostering open skies policies among AU member states by eliminating non-physical barriers.

However, more than thirty years have passed since the initial declaration of the ‘Yamoussoukro Decision,’ and twenty years after it became fully binding, progress has been disappointingly limited. Only a few instances applying the principles outlined in the declaration have been observed or put into practice. Signatory states have struggled to establish the necessary mechanisms for dispute resolution, anti-competition regulations, and the creation of a regulatory body responsible for monitoring and oversight. Additionally, the majority of African countries have adhered to restrictive traditional bilateral agreements, undermining the fundamental purpose of the declaration. Currently, there are over 600 bilateral air service agreements (BASAs) across the African continent, although most of them do not comply with the provisions outlined in the ‘Yamoussoukro Decision’

The current state: Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM)

In light of the sluggish implementation of the ratified ‘Yamoussoukro Declaration’ by individual states, and with the aim of expediting intra-African trade and integration within economic blocs, the African Union (AU) adopted an ambitious initiative in 2015 known as ‘Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want.’ This Agenda serves as a long-term strategic master plan (spanning from 2013 to 2063) that prioritizes inclusive social and economic development, continental and regional integration, democratic governance, peace, and security, among other critical issues aimed at positioning Africa as a dominant player on the global stage.

Agenda 2063 revolves around 15 key flagship projects, programs, and initiatives that have been identified as catalysts for Africa’s economic growth and development. One of these flagship projects is the Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM), which was formally launched on 29th January 2018. SAATM is currently being advocated and spearheaded by the African Union Commission (AUC), the Africa Civil Aviation Commission (AFCAC), and the ministerial working group. Its primary objective is to establish a unified market for intra-African air transport connectivity, promoting the liberalization of civil aviation in Africa and serving as a driving force for the continent’s economic integration agenda.

The implementation of SAATM is believed to enhance intra-regional connectivity in Africa and promote the development of the aviation sector, tourism, and trade. Eligible African airlines would be able to operate routes based on their own economic considerations without any hindrance, as stated by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA).

In the short term, SAATM focuses on encouraging member states to amend and align their existing Bilateral Air Service Agreements (BASAs) with the provisions of the Yamoussoukro Declaration (YD) to boost intra-Africa trade. The operationalization of SAATM is considered a facilitator and enabler for the success of Agenda 2063 and other flagship projects such as the Africa Continental Free Trade Area (AFCFTA). The AFCFTA aims to utilize and accelerate intra-Africa trade as an engine for growth, sustainability, and positioning Africa’s trade in the global market.

Another complementary flagship project to SAATM is the Africa Passport and Free Movement of People (APFMP), which seeks to remove restrictions on Africans’ ability to travel, work, and live within the continent. This initiative aims to transform Africa’s laws, which currently have generally restrictive policies on the movement of people, despite commitments to dismantle borders and promote visa issuance by member states, thereby facilitating the free movement of all African citizens across the continent.

Acceleration of SAATM

To expedite the implementation of SAATM, the Africa Civil Aviation Commission (AFCAC), as the executing agency, launched the Single African Air Transport Market – Pilot Implementation Project (SAATM-PIP) in Dakar, Senegal in mid-November 2022 during the 23rd Yamoussoukro Decision Day (YD-Day) commemoration. SAATM-PIP aims to accelerate the implementation of the initial initiative that started over thirty years ago in 1988. The launch of SAATM-PIP was prompted by the slow progress and limited breakthroughs in the liberalization of the African airspace, despite various milestones and initiatives launched in support of deregulation.

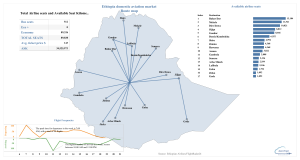

The primary focus of SAATM-PIP is to identify and select countries that have the most favorable conditions (referred to as SAATM enablers) and are willing to enter into YD-aligned or YD-compliant bilateral air service agreements (BASAs) with each other. According to AFCAC, 35 out of the 54 African countries, accounting for 85% of intra-Africa air traffic, have unconditionally committed to implementing SAATM. Among them, 21 countries have signed the Memorandum of Implementation for the operationalization of SAATM. However, only 19 states have endorsed the SAATM-PIP cluster1 through signature.

The countries that have signed SAATM-PIP are as follows, categorized by their respective regions in Africa: Central Africa – Cameroon, Central African Republic (CAR), Republic of Congo, and Gabon; Eastern Africa – Ethiopia, Kenya, and Rwanda; Northern Africa – Morocco; Southern Africa – Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, and Zambia; Western Africa – Cape Verde, Cote d’Ivoire, the Gambia, Ghana, Niger, Nigeria, and Togo.

With the launch of this ambitious initiative, the goal of liberalizing the African airspace is closer to being achieved. SAATM-PIP represents the best opportunity to finally implement the Yamoussoukro Declaration (YD) after years of concerted efforts.